Remember…

when you subscribe to Midjourney or you go for that OpenAI plus subscription, you are not just accessing a service. You are endorsing the acceleration of research and development of AI systems.

With your subscription, you are sending a message that will be heard loud and clear across the world: whoever develops a system stronger and faster than all the rest will be rich and powerful.

To throw fuel on that fire without simultaneously cutting off its air is unethical. And would doing that even be enough? Should we cut off both its air and its fuel too? Ask yourself this question:

If we don’t know how it works, and its implications are arbitrarily massive, should we accelerate its growth?

To put it another way, how much do you trust tech bros or politicians? I suspect the answers to both those formulations are strongly negative. Well, so what, then? Cancel the subscription? Sit this one out? Find an ingroup of non-users where you can assuage your FOMO by loudly criticising the sheeple hurtling past on the way to the cliff top?

I don’t think that’s very smart either. It’s uncritical because it fails to differentiate between the good and the bad aspects of the technology, and requires for validity an assumption that the world contains a critical mass of idiots. Actually, that might be true. At least, I don’t think any thinking person would want to gamble on the odds, so there has to be another way.

A moratorium seems plausible at first, but as far as I can tell there isn’t much chance of it happening because it would only take one deregulation fan to break ranks. Rather, it wouldn’t happen unless a disaster that was barely averted but still very serious precipitated it. It would have to be bad enough for the international community to “come together to ensure this can never happen again”, but not so bad that our collective reason-making is mortally harmed.

That’s the top-down model of starving the fire of air. What about a bottom-up model? This is perhaps more plausible, though it would require collections of people to act contrary to some key reward loops. How would that contrariness look?

Be critical. Reflect. Ask, what am I doing with AI? What am I trying to get out of it? How am I allowing it to affect me? Ask yourself what you have used AI for so far? Aside from just playing around to see what would happen, what have you done that you couldn’t do before?

So far, I’ve used three AIs. Midjourney I’ve employed to create concept art for a character design for a story I’m putting together. I’ve also used it to generate art for building a website.

Notion AI, powered by GPT3, I’ve used to review the text in some documents and pull out a list of stakeholders referred to in each.

And GPT4 I’ve mainly used to assist in programming the abovementioned website. If I need a certain feature and don’t know how to do it, GPT4 shows me the tool to use or writes some CSS. I’ve also asked it to suggest ideas for documents I’m writing and to propose readability and formatting edits to a document I’d already written.

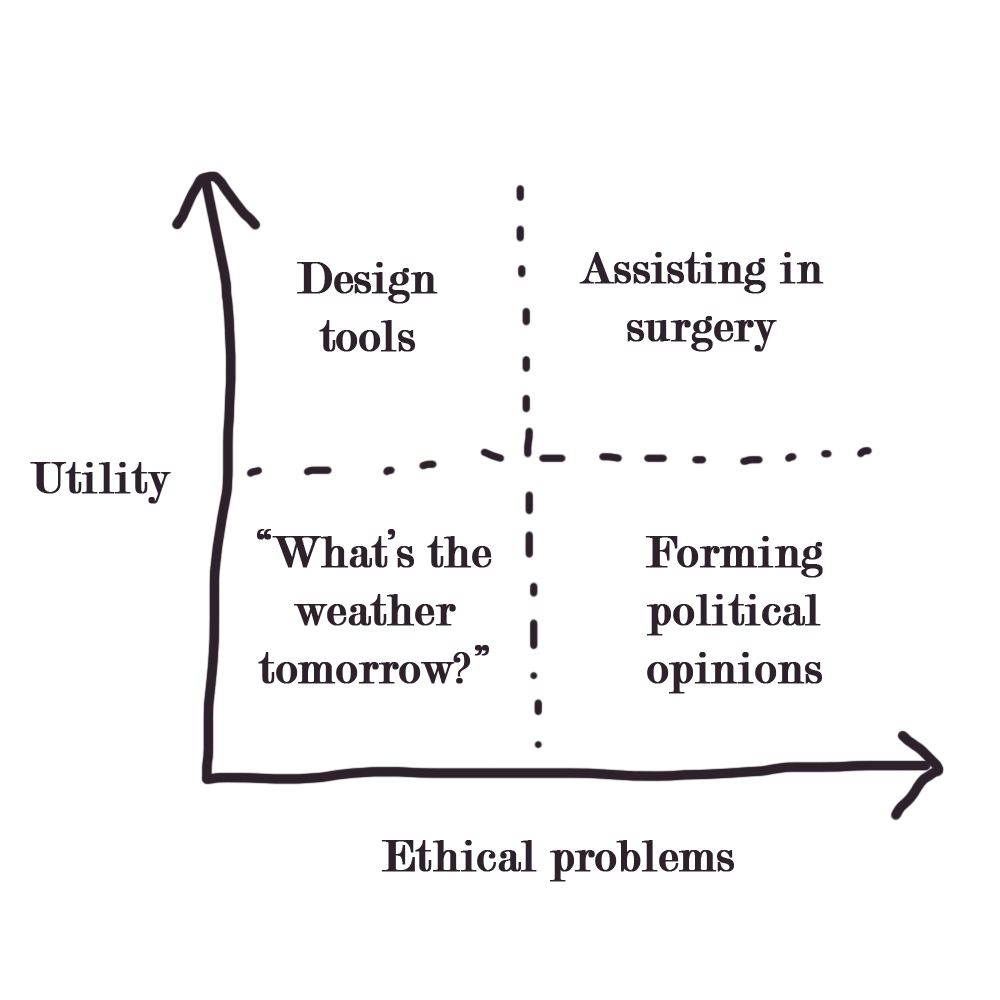

This is how I intend to use AI for the foreseeable future: as tools to help me design and make stuff I otherwise couldn’t. None of this is free of ethical dilemmas, such as cumulative error that causes some kind of drift over time, but they seem technical, measurable and, at least in comparison to some others, small dilemmas.

I’m not going to ask GPT4 how I should live, what I should believe in, what I should think of other people or anything at all that has real implications. If GPT is wrong about where a particular WordPress tool lives, or how it works (and it has been repeatedly so far) it doesn’t matter. I can tell it it was wrong and it can try something else. These cases are low stakes and falsifiable. GPT4 says “enter such-and-such in this field” but there is no field there? That’s fine. Mistake caught. We can correct, not that it matters greatly in any case. But if I ask for something that is fundamentally an opinion, or isn’t easily falsifiable, and start making a habit of it, I extend its effect to a different place in society altogether.

If I may, I’d advise you to consciously frame these systems as design tools. Use them for concept ideation, for coding (though keep an eye on that), for copy editing. Lower your expectations. Resist any tendency to outsource your search for truth.

And that brings us onto the thorny question of consciousness itself. I don’t like that this is even a topic of discussion, that “the day they warned us about is finally here”, because the whole issue is unhelpful and a part of the mythologising.

My view on this is that the hard problem of consciousness is impassable. We don’t have, and never will have, an ability to say whether a system has a subjective experience based on what it tells us or what we observe. GPT4 is a closed box filled with patterns that are modelled on human behaviour and guided by human reinforcement learning. It is a blind-spot shaped object sitting within our blind-spot because that’s the way we designed it.

It isn’t conscious. Its reconstruction of human psychology doesn’t imply consciousness any more than a portrait’s resemblance to human anatomy implies consciousness. And for that matter, structural resemblance to a real brain doesn’t imply consciousness either, as a brain can be unconscious and the body’s heart will still beat, the chest will still rise and fall. People can even talk and move in their sleep when they have no subjective experience. The mystery is not whether an AI has consciousness but why animals aren’t unconscious the whole time like everything else. My guess is it conveys an evolutionary advantage, but as AIs don’t have genes or reproduction that doesn’t apply to them anyway. Perhaps this is really just kicking the question down the road, in any case, as it’s about the mechanism by which consciousness arises, not what it’s for once you’ve got it.

I would liken AI to a sunflower. Sunflowers are heliotropic; their heads turn to face the sun. When you look at a sunflower, because it is a flower and you know flowers, and because in the sky above is the sun and you know the sun, it’s intuitively graspable that it’s just a flower doing flower stuff.

However, if neither flowers nor the sun were part of your experience, you might try to understand what you observed in terms of a collection of plant cells with subtly varying hydrostatic pressures, which work collectively in response to particular qualities and quantities of radiation, incident from a giant ball of radiant particles hovering some great distance away in the cosmos.

Imagine that a sunflower were five, six, seven orders of magnitude more complex a system than it is, too complex for it to be possible to intuit even with a lifetime of experience. You would see an unknowable thing that turns to face the light above, and possibly conclude that it intends to do so, that it likes facing the sun, and that it’s therefore conscious. You would afford it an imaginary subjective experience, extend rights to it in order to preserve that imaginary experience. And, of course, you’d be mistaken. It’s just a collection of plant cells that happen to move like a thing would move if a person moved it.

Aside from the vanishing unlikelihood of consciousness occurring, I think there may be an ethical case for a collective decision on our part that AI is not conscious even in the absence of being able to prove or disprove it. In terms of our relationship to this technology as a species, our derangement will be far smaller if we view it as only technology – a suite of tools useful in design, coding and copy editing – and not as a sage, an oracle or a god.

The more mundane its use cases, the more we will retain a healthy, and not a toxic, relationship with it. We will cool the fire. AI corrects your formatting. It jazzes up a blog header. It generates concept art. These capabilities will expand over the coming years, but I believe they remain the most apposite (and in some ways even most compelling) use cases, in part because I can see a direct correlation between the use of an LLM that talks or paints like a human and the output delivered; it’s not some ambiguous component of an opaque system applied onto my life from above as it might be with, say, banking or air traffic control or schooling.

But there’s a problem, isn’t there? Perhaps you’ve spotted it already. This website celebrates the spectacle of AI generation. It presents the most attractive, striking visuals. It fosters a sense of community where visitors can play, if they’re so minded, the game of being genAI early adopters, part of the team that’s going to win, part of a special club of smart people who are going to the moon.

How can we do that without generating hype? How can we put posts on Instagram, simultaneously hoping they’ll get clicks and hoping that the bigger picture organises itself as though they hadn’t?

The only way I can think is that we must provide a little fuel to generate heat, and keep tight control on the air flow. A nice, cosy log burner, if you will, rather than an oil well inferno where the whole world’s a sea of oil. If we can foster a community of people who view AI primarily as a design tool, and who remain detached, cool-headed and cautious in the face of mythologising, we will have been a force for good in a world that is changing, and in some ways for the better.